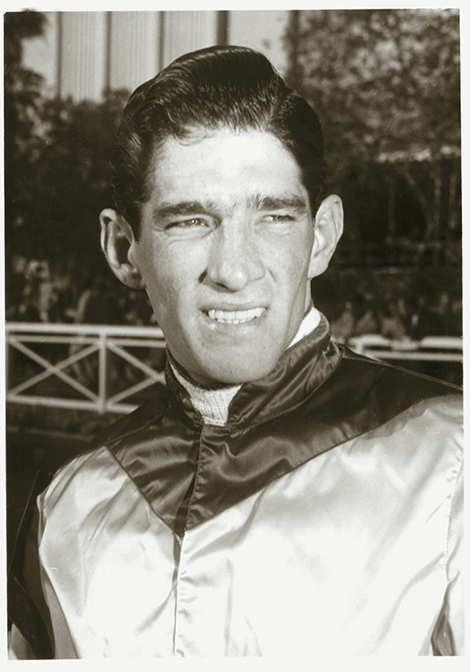

Manuel Ycaza won his second Florida Derby in 1969 with Top Knight (Blood-Horse Archives)

I first profiled Hall of Fame jockey Manuel Ycaza in 2009 when Churchill Downs' old website was running a series called "On The Muscle" and Ycaza's four victories in the Kentucky Oaks (gr. I) merited a trip down memory lane. A look through the clippings files at Keeneland Library and a visit to the Sports Illustrated and Time Magazine vaults gave ample background for the interviews I conducted with the former rider; old-time turf writers were captivated by Ycaza's story and provided a wealth of coverage still available today (like this Saturday Evening Post feature by Sandy Grady). My own piece ran again in December 2011, this time on ESPN.com. It remains one of my favorite articles, thanks to the rich and vibrant nature of Ycaza's fascinating--and pioneering--career.

Looking through records of Florida Derby winners leading up to this year's edition, I saw a familiar name in the rider column. Ycaza took this key Kentucky Derby prep twice; in 1962 on Ridan and in 1969 aboard Top Knight. By the second victory he was close to sustaining the injuries that would result in a premature end to his career in 1972 (although he came back in the '80s before hanging up his tack for good). When he won the race for the first time, he was still a controversial figure in the irons--and thanks to a win in the Florida Derby, Ridan would be positioned to go down as a part of that history.

Flash back with me. Spring of 1962. The target everyone wants to hit, of course, is the Kentucky Derby--but in the meantime, as a stepping-stone, Gulfstream Park's big event looms.

"They had very few prep races," Ycaza recalled. "Now they have prep races everywhere. It's a little bit different because there's more variety now. When you ride, it doesn't matter what kind of race; you want to win it, but you don't want to overdo it when it comes to using your horse, because you're trying to bring them gradually to a peak. In Florida, some of the small events going into the Flamingo were very important, so you could have your horse ready to win the Flamingo and then the Florida Derby. And then, if you happened to win both or either, knowing that you still had some left, then you were thinking ahead because this horse has beaten the opposition coming into the Kentucky Derby. So winning or doing good with a horse if he wasn't in any trouble at all, during the Flamingo and the Florida Derby, you knew he was something special."

Ridan was one of the best juveniles of 1961, a son of Nantallah who had been purchased by trainer Moody Jolley from Claiborne Farm as a yearling and who was trained by then-youngster LeRoy Jolley. Unbeaten in seven starts in 1961, including Arlington Futurity and Washington Park Futurity wins, the big bay colt was piloted by Bill Hartack through his early starts. In fact, Ycaza's first time in the saddle was for a get-acquainted workout before the Florida Derby, during which a mishap with the saddle caused moments of concern and the rider's natural horsemanship came in handy.

"He was a huge horse; he must have been over 1,200 pounds," Ycaza said. "I remember before the Florida Derby I worked him out between races and they sent a lead pony with me. When he lunged to work, I think it was a mile and an eighth or a mile workout, one of the (stirrup) leathers on the outside of the saddle came out. You had a lock, like a safety, and for some reason it wasn't properly secure and the whole leather came out. I just kept my other foot in the stirrup and I worked him out; it wasn't bad because I was used to riding horses without any stirrups, bareback, I worked them out that way when I was young."

By the Florida Derby, Ridan was no longer invincible. He'd won the Hibiscus Stakes, his 3-year-old debut, in record time--but was then beaten in the Bahamas, Everglades, and Flamingo. The colt had been a front-flying speedster, and Jolley was convinced he could come from off the pace to regain his winning ways. It would be Ycaza's job to teach him to do so.

"It wasn't a problem to rate him at all," Ycaza remembered. "He had a decent workout, and I had a feeling for him. But he was up against against a pretty nice filly, Cicada, and it took life and death to beat Cicada that day, so I wasn't really impressed about his abilities. If he's going to take life and death to beat a filly, even though I knew Cicada was a pretty good filly--she was probably the best of her generation--but I figured Ridan should have beaten this filly easier in my book, so I wasn't that impressed even though I won the Florida Derby."

The Blood-Horse recap of April 7, 1962, recounts the thrilling victory Ridan eked out over Meadow Stables' champion Cicada: "Eleven 3-year-olds went to the post in the (Florida) Derby, but it was strictly a two-horse race--and a great one...Ridan and Cicada brought off another dramatic finish that kept the crowd of 25,270 in a state of high excitement from the quarter-pole to the wire."

Ridan and Cicada provided a Florida Derby thriller in 1962 (Blood-Horse Archives)

Then came the Blue Grass Stakes, which Ridan won handily to establish his status as the heavy favorite going into the Kentucky Derby.

"I rated him right behind horses," Ycaza remembered. "I let him break out of the gate and instead of sending him, I put my reins down sort of like relaxing away with him--but then snugging him so he could feel the bit. I never believed in totally relaxing a horse; I always played with them, more or less, keeping a feeling. He was behind horses the first part of the race. There was an opening on the rail passing between the three-eighths pole and quarter pole, and I just cut the corner and then he went on and won the race with authority. I was very impressed in the Blue Grass. Very impressed. That's the final prep before the Derby, and I said to myself, 'Manny, how sweet it is. You have something good.'"

There was no question Ridan was best in the Blue Grass Stakes (Blood-Horse Archives)

Unfortunately, Ycaza and Ridan didn't capture the Run for the Roses. A final workout in Louisville gave the jockey cause for concern when the colt kept trying to get out. That negative action continued when the gates opened on Derby day.

"Instead of changing leads properly though the turn, he was bearing out," Ycaza said. "The workout was decent, but I was concerned because he was trying to get out real bad, and I didn't like that sign; obviously something was bothering him. Came the Derby, it was a large field; he broke decent and now it's not a matter of rating him--he's in the middle of the track and he's bearing out real bad. I'm fighting him the whole mile and a quarter just to keep him in, never mind to let him run. In that case, I'm trying to make him change leads so he can just run comfortable. Well, anyhow, to make the story short, he finished third in the Derby, pretty much in the middle of the track, and I fought him the whole mile and a quarter. Decidedly won that Derby. I wasn't pleased at all, not only because I didn't win the Derby, but because the horse didn't run the way he should have. I was disappointed because in my estimation he lost the Derby because I couldn't ride him comfortable. Using my left arm to try to keep him in, and in the straightaway trying to ride him and keep him in at the same time, it was almost an impossibility. For almost a week my left arm was so sore, it practically felt like it was paralyzed.'

You've probably seen this award-winning photo by Baltimore Sun

photographer Joe DiPaola; it ranks right up there with "The Savage," a

shot of Great Prospector biting Golden Derby during the 1980 Tremont

Stakes, for dramatic finish-line captures. Ridan was the horse and Ycaza

was the jockey, and as the now 75-year-old rider said when I called to

ask him about these horses, "Well, you know what happened there."

The Preakness photo caused great outrage among members of the racing media, including the great Whitney Tower, who ripped Ycaza's ride to shreds in his gamer, "Courage Beats Gall."

Here's what Ycaza said about the incident: "In the Preakness he didn't really have any problem. I was taking him behind horses, and his behavior was pretty much like in the Blue Grass. Coming to the turn, I just cut the corner and took the lead. I was the type trainers didn't give much instruction at all. I knew exactly what I was doing on a horse. But before the race, Moody Jolley said, 'Manny, whatever you do, don't finish on the inside.' And I didn't like that at all because I used to hate to give ground to anybody. There was a brush, pretty much, at the end of the race--because I left the rail. But if I hadn't been told that, I would have never left the rail. I left the rail and Greek Money came in there and you know what happened. I came back to close it up, simple as that. And then they asked me to claim foul. I would have never claimed foul, never in a million years, because everybody used to take a shot toward me because of my reputation. I would have just said, well, that's the end of the race, that's it.

"I was disappointed," the jockey continued. "I know the opposition. I know the horse. I know the style of riders, the idiosyncrasies of the trainers, the instruction, I know all of that. So in the end, you have to move on. You chalk it up to experience."

Top Knight's Florida Derby win was an impressive romp (Blood-Horse Archives)

By the time Ycaza rode his second Florida Derby winner, he was firmly established as one of the sport's premier riders. He had won the Belmont Stakes in 1964 aboard Quadrangle, upsetting Northern Dancer's Triple Crown bid (they also went on to win the Travers together, which Tower brilliantly captured here).

Ycaza's fortunate association with Capt. Harry F. Guggenheim, former U.S. Ambassador to Cuba and a founding member of the New York Racing Association (and publisher of Newsday), also proved mutually beneficial. Guggenheim's Cain Hoy Stable runners were primed to take home every considerable victory--and Ycaza helped make him the leading owner in the nation.

Among the legendary horses Ycaza piloted to victory were Sword Dancer,

Gamely, Silky Sullivan, Ack Ack, Dr. Fager, Damascus, and Fort Marcy--and in 1969, Top Knight appeared on his way to joining their ranks as a legendary contender. The son of Vertex raced for owner Steve Wilson to victories in the 1968 Hopeful, Futurity, and Champagne Stakes and was the champion 2-year-old of that season for trainer Ray Metcalf. He came into the Florida Derby after rocketing back from a disqualification in the Bahamas Stakes and a runner-up finish in the Everglades by taking the Flamingo in convincing style, and won Gulfstream's prep for the Run for the Roses by five lengths, a then-record margin, over Arts and letters and Al Hattab. Sadly, Wilson died five days before Top Knight galloped to what would be his last win. The colt was highly-regarded heading into the Kentucky Derby (I enjoyed this article from the Times Record on his early days as a yearling), but it would be won by Majestic Prince that year.

"He was a nice-sized horse; he had a nice temperament," Ycaza recalled. "He used to break alert out

of the gate, and you could place him. Those kinds of horses are ideal

because you don't have to fight with them. If there's no

pace, you can put them on the front and just set your own pace. If there

is pace, you can just lay behind, save ground, or whatever. In

that respect he was ideal.

"Going into the Kentucky Derby, I thought he was going

to be probably my best mount. I beat Arts and Letters in the

Flamingo and Florida Derby, so I wasn’t worried too much about him even though I knew that he was a good horse. But my horse wasn’t a sound horse.

Ray Metcalf used to train him very carefully because he had a very

questionable tendon, so you had to ride this horse with kid gloves.You cannot

have any horse near him to bump him, and even though I hated to lose ground, every time I rode him, up to the Derby, this horse was always in a clean spot just to make sure he wasn't in trouble at all. I used to ride him very, very precise, giving him a chance to switch leads, and then gradually set

him down without really forcing him because of this condition. I used to ride him with very, very tender hands.

"In the Kentucky Derby, he was in a real good spot. I left

a little opening on the rail so my horse could change leads coming into the turn, and

that way I knew he was going to make it clean. Going into the last turn, Braulio Baeza came with Arts

and Letters on the inside, where I'd left that hole. He got through and

he brushed me, and my horse switched leads and that was the end of it. He

stopped right then. He was running like a million-dollar horse that day in

that Derby, but as soon as he got brushed, that was

the end of it. He finished fifth, and I rode him again in the Preakness,

but he was not the same horse."

Manuel Ycaza helped pave the way for today's riding stars (Blood-Horse Archives)

Almost incomprehensibly, given the number of classic racehorses he rode and the victories he amassed, Ycaza never quite managed to collect a Kentucky Derby win. That, however, is no black mark against his legacy. He survived not only the evolution of the sport through the glory days, but an integration movement that sportswriter William Leggett termed "The Latin Invasion," that period of time when groundbreaking riders changed the diversity of the jocks' room. Those who look back upon his remarkable career will recognize how he helped paved the way for his fellow Latin Americans. His influence may also be seen in young riders today.

"There were good riders before my time

when I came here, but when I came over here, I changed some things," Ycaza said. ""(Eddie) Arcarao used to be a supreme rider, but he used to rock in the

seat; there was a rocking movement of the stirrup and the body. He

looked great doing it, but that wasn't my thing. I was usually very still on a

horse. Now that's prevailed and most riders are the same. Riders didn't switch whips at all when I came here, and when I

was in

Mexico City the same way and when I was in Panama the same way. If you

were

a right-handed jockey, you rode and hit

right-handed. If you were left-handed, the same thing. I happened to be

an athlete before I became a jockey. I was riding horses bareback with

my brothers all over any farm. I used to play baseball, soccer, bicycle

competition; I was in boxing, I was in everything. I used to hit

left-handed and right-handed, I used to do it as an automatic thing. I

couldn't understand why they hit one way without trying both ways. When I

started, I was doing that automatically. I was hitting right-handed,

switch, left-handed. When a horse lugged in, hit him left-handed, vice

versa. When I came here, there was a handful of jockeys that used to

switch the whip, but they used to put it in their mouth. Arcaro was one

of those who switched sticks. A few did it, but they were very, very

few. They used to put the whip in their mouth, and a

lot of times I used to knock the whip right out of their mouths. It was

such a simple thing.

"Now, everybody switches sticks, but the problem is they

don't use the whip when it counts; they use the whip for the heck of

it. There's no reason why you have to switch the whip at the head of the

stretch three or four times, for what? If the horse is not responding,

you do more harm by overdoing it.

"A jockey cannot ride faster than a

horse can run," he said. "You're there for one reason: to try to help this horse to

get the best of the situation. Just to help him, that's why

you're there. You are part of the horse, and

you're trying to guide him. To me, riding is a very simple thing--common sense. It's not difficult."