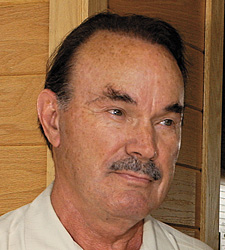

With their signature mustaches, brothers Art and Jack Preston often get mistaken for one another by racetrack officials and reporters who don’t know them well. So after Art’s 5-year-old horse Flat Out won the Suburban Handicap (gr. II) at Belmont Park July 2, it was Jack who was supposedly getting quoted in the media about the big victory.

With their signature mustaches, brothers Art and Jack Preston often get mistaken for one another by racetrack officials and reporters who don’t know them well. So after Art’s 5-year-old horse Flat Out won the Suburban Handicap (gr. II) at Belmont Park July 2, it was Jack who was supposedly getting quoted in the media about the big victory.

“Yeah, he got a big kick out of that,” said Art Preston, who campaigns the son of Flatter under his Preston Stables banner. “We take turns—I’ve been out in California where people will congratulate me on a great win they think I had out there with Jack’s horse, and I’ll go ahead and tell them how I did it.”

There is little mistake about the Prestons’ impact on Thoroughbred racing. Along with their late brother J. R., the Prestons raced Victory Gallop to win the 1998 Belmont Stakes (gr. I), denying Real Quiet the Triple Crown. They also co-owned Da Hoss, who made history by taking the 1996 Breeders’ Cup Mile (gr. IT) and returning two years later, with just one race in between, to repeat in 1998.

The brothers entered racing after success in the oil business in Texas, where they formed Preston Oil in 1970. It turned out to be the perfect primer for their Thoroughbred interests.

“In the oil business you get a dry hole and lose 80% of the time,” Preston said. “It’s like racing—if you persevere, you’re going to hit the big one.”

Art Preston entered the Thoroughbred world in the late 1970s when he bought a piece of a $10,000 claiming horse named Old Sew and Sew, a son of Ole Bob Bowers, who became famous as the sire of the legendary John Henry. The three brothers established Preston Farm near Quanah, Texas, and, more notably, Prestonwood Farm near Versailles, Ky., which they sold in 2000 to Kenny Troutt and Bill Casner, who renamed it WinStar. The Prestons’ champion sprinter Groovy was one of the first inhabitants of their Kentucky breeding shed. They also brought in Distorted Humor, in whom they owned a half-interest with Russell Reineman. Distorted Humor has proved to be one of the world’s top sires and still stands at WinStar.

Since selling the farm, Art Preston has downsized his equine operation but still maintains a formidable stable, buying from 15-30 yearlings per season and selling perhaps half as 2-year-olds while campaigning the remainder. He has 15 2-year-olds today and a like number of older horses in training around the country with various conditioners. Preston’s Birdrun, a son of Birdstone, captured the Brooklyn Handicap (gr. II) at Belmont in June and seems a logical contender for the Breeders’ Cup Marathon (gr. III).

Also, his Central City is returning to the races after time off to fix a breathing problem. Central City is a talented sprinter, having won the Jim McKay Turf Sprint last year and finishing second in the Breeders’ Cup Turf Sprint (gr. IIT) at Churchill Downs last November. He has banked $339,000 thus far.

“Hopefully, we’ll have representation in the fall (at Breeders’ Cup),” Preston noted.

The stable star for now is Flat Out, who was on the Derby trail in 2009 after winning the Smarty Jones Stakes at Oaklawn Park. However, foot problems and unplaced finishes in the Southwest Stakes (gr. III) and Arkansas Derby (gr. II) earned him some time off.

“He came up with quarter cracks in several of his feet, and it’s been an ongoing problem,” said Preston. “He’s never been sound enough to show the potential we thought he had.”

Preston paid $85,000 for Flat Out as a yearling, and he’s returned nearly $360,000 in purse earnings. This season he began with a good second to Awesome Gem in the Lone Star Park Handicap (gr. III), then finished sixth in a deceptively good performance in the Stephen Foster Handicap (gr. I) prior to the Suburban.

“He had the inside post and was trapped down there the entire race,” said Preston. “It was the worst place to be that day, and he still got beat only 23⁄4 lengths. We were still very game about him. He bounced right back after the race and wanted to go again, so we went to the Suburban and he got the trip and liked the track.”

After the race Preston joked that it was only the second time he’s taken money from Belmont Park back to Texas, referring to Victory Gallop’s earlier triumph.

“I should have said ‘from New York City’ because like most entrepreneurs, I’ve gone up there forever trying to raise money from those guys (investors), and I’ve never gotten any from them, so I have to get it from the horses.”

Preston is aided by Rich Decker, who ran Prestonwood Farm, and by Frank Bettencourt, the farm trainer at Preston’s facility near Paris, Ky., who breaks the babies and trains them up to the 2-year-old sales or the races. Preston’s farm is the former Golden Chance Farm.

“I’m about at the size I need to be with the horses,” said Preston, who is no longer in the breeding business. “It’s a numbers game, and you can’t get the big horse unless you’re buying some. It’s smaller than it used to be, but I’m pleased with it now.”