The charm of horse racing lies primarily in the animals that do it—their beauty, grace, power and their degree of class. But there is an undeniable attraction to the colorful human beings that make it happen. The purpose of this blog is to share my stories about some of these characters. My requisites in the selection: I had dealings with them, their antics and accomplishments should not be forgotten, and that at least most of them are

no longer with us. — Cot Campbell

I have dealt with a number of America’s greatest horse

trainers. None evokes more delicious memories than Angel Penna.

Angel Penna was a son of Argentina,

but as a horseman he was international in every sense of the word. Linguistically,

he took a crack at three different languages, sometimes simultaneously! He was

surely one of the greatest Thoroughbred trainers who ever lived and also one of

the most challenging with whom to communicate.

He trained

stakes winners Law Court, Montubio, and Southjet (the latter two winning grade

I’s) for Dogwood Stable.

Never in my

relationship with him did I know exactly what the hell he was talking

about.

That’s an

exaggeration because somehow he managed to be a most delightful and expressive

companion. He had a marvelous sense of humor, and he was very witty (I think). His

face helped immeasurably because it was constantly and eloquently assisting

with his dialogue. There were fearsome scowls, moments of beaming exuberance,

beatific benevolence, vigorous rolling of the eyes, glances heavenward to

invite God’s sympathy, weary looks of resignation, and constant shoulder

shrugging. All of these were accompanied by guttural grunts and a strange

quasi-tap dancing shtick to help sell his point. You eventually got the gist of

all this pantomime.

One of our

horses, Montubio —once suffered a severe case of colic. The vet was summoned. He

oiled him in an effort to unblock the impacted bowel. The treatment was

successful, and soon the horse was able to eliminate waste material.

When I

called Angel to ascertain the horse’s condition, I was delighted to hear the

lilt in his voice and to get his down-to-earth report: “Oh, he ees very fine

now. He have many uh…uh…poo-poo!”

Angel

defined the word volatile yet was as kind a fellow as you would ever know. An

unforgettable character.

He looked

like my idea of a dashing, decidedly upscale gaucho. Angel was of moderate

height but had short, bandy legs attached to a torso belonging to a bigger man.

He was heavy, not fat, and strong, with very wide shoulders. Penna’s face was

weathered, with a prominent nose and bright, intelligent eyes. His hair,

beginning to thin, looked as if it had been painted on his head.

Penna was a natty dresser. No blue jeans for him. He wore cavalry twill trousers, a smart

checkered shirt with an ascot or, at least, a colored handkerchief knotted

debonairly around his neck. He usually wore a sport coat. His paddock boots

were shined daily, by someone in the barn, I would imagine. This was a trainer

who would probably be attired in a dark blue business suit when he saddled a

horse. He had style galore.

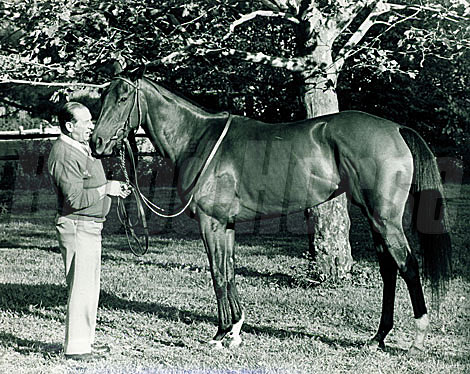

Angel Penna with Blitey (Courtesy of NYRA)

Order This Photo

Penna trained in Argentina, Venezuela, France, and America and produced champions in

the latter three. He won practically every great race in Europe, including two

Prix de l’Arc de Triomphes (Fr-I) with the fillies San San and Allez France.

San San’s regular ride was Jean

Cruguet, but he had been injured five days before the Arc and was replaced by

Freddie Head. After winning the race, Angel first went to find Cruguet. He

cupped the rider’s face in his hands and tearfully commiserated that the

sidelined jockey had not been able to experience the thrill of this victory. Never

mind that a week earlier Angel might have chased Cruguet out of the stable yard

in a towering rage.

Penna won

practically every great race in Europe except the English Derby (Eng-I), and

many great races in this country but not the Kentucky Derby (gr. I).

Over here

he trained for Ogden Phipps, Gus Ring, Frank Stronach, Dogwood, and Peter Brant

among others.

His wife

aided him enormously. Elinor Penna served as sort of a conversational

facilitator, explaining a little here, cuing Angel at certain times, and

defusing when necessary. She was a former sports commentator, a keen student of

the racing scene, well-connected socially, and a wit of the first dimension.

Angel sired

a son, Angel Jr., to whom he was devoted. This Penna is now one of America’s

most prominent trainers.

Talking on

the phone with Penna was the most difficult form of communication because you

were robbed of the visual aids. When “call waiting” was first offered, for some

reason Angel, who really did not relish talking on the phone, ordered it on his

barn line. This service threw him into a constant tizzy, and he switched in

confusion back and forth from one caller to another, often pursuing the wrong

subject with the wrong party and usually disconnecting both parties.

Elinor

puzzled, “I don’t know why he wants to tackle two callers. He can’t even talk to one person on the phone.”

I once gave

Angel a gigantic Nijinsky filly to train. Her name was Helenska. He took a long

time with her, as he was prone to do. Of course, I wanted to get a line on her,

and I periodically sought his opinion.

“What do

you think of this filly so far, Angel?” I would ask from time to time.

“Ahhh! Too

beeg…too beeg!” he would exclaim, throwing his arms and head skyward, to seek

devine assistance.

The filly

bucked her shins finally, and I took her back to the farm to be fired. When she got over this ailment, I decided to

send her to another trainer because I was convinced Angel did not like her (Is

that not what “too beeg…too beeg” implied?).

She did go

to another barn. When Angel recognized her training on the racetrack one morning,

he went ballistic. It seems he loved the filly all along, was looking forward

to getting her back, and was crushed that I had insulted him by sending her to

another man.

He called

me up and “fired” me, told me to remove my horses from his barn. Knowing this

storm, legitimate though it may have been, would blow over soon, I phoned the

next day and was finally able to smooth his ruffled feathers. This was one time

when Elinor’s interpretive services were badly needed.

He was

truly an internationally renowned trainer and had ruled the roost on three

continents. He was the man! He knew

it, and his barn knew it. It was run with the precision of West Point. His

staff adored him, struggled to please him, and treated him like a king.

He was at

his barn 14 to 16 hours a day. When the Allen Jerkenses and the Pennas went out

to dinner, four cars were necessary. Both Elizabeth Jerkens and Elinor Penna

knew that Allen and Angel would be going back to their barns for an hour or two

after dinner.

Amazingly,

Penna could get a horse ready to run a mile and a quarter—and win—first time

out. Inexplicably, he never seemed to breeze the horse. He had what he called

“happy gallops,” which were just that: exuberant, open gallops that lasted maybe

a half-mile, but more likely a quarter-mile. There was nothing noteworthy or

detectable in his training regimen that would explain this singular magic. And

you sure as hell couldn’t ask him. He might take a long time to get a horse

ready to run, but when his horses were led to the paddock, they were ready to

crack. His horses were happy and they were fit, or they weren’t put in the

entries.

He liked to

ride Vasquez, Bailey, and Cruguet, and he loved Angel Cordero, who had a flair

for kidding him into a jolly frame of mind. But one time Cordero could not.

Penna had

brought to this country a very good horse named Lyphard’s Wish. The colt was

ready for his first race, and Angel Cordero would be riding him.

Penna was

not noted for his precise riding instructions, but he knew exactly what he

wanted. According to Cordero, Penna’s

instructions were something like, “Don’t take no hold. If they walk, you walk. If they go fast, you

walk. When you get there…you move!” If this is verbatim, one can understand the

jockey’s confusion (although Cordero never paid any attention to instructions

anyway!). Cordero swore that Penna

always instructed to “move when you get there.” But he never said where “there”

was!

This day

Lyphard’s Wish, fresh and running for the first time in strange surroundings,

roared out of the gate, hit the front, and ran off with Cordero. At the

sixteenth pole, the rank horse was out of gas and got beat, thoroughly

embarrassing Cordero and infuriating Penna in the process.

When the rider

dismounted and weighed in, there was Angel Penna doing his little jig of rage.

The veins in his neck were distended, he was flinging his arms about, and his

visage was wreathed in wrath. He sputtered for words powerful enough to

express his utter contempt for Cordero’s ride.

“What you

do? What you do? You ride thees horse like a uh, uh, black man!” The Puerto Rican Cordero replied, as he

walked with the trainer back toward the jockey’s room, “Well, hell, I am a

black man. What do you think these are—blonde curls?”

Angel Cordero thought it was funny.

So did Angel Penna—about two days later.

More of Cot Campbell's stories are included, among a host of others, in The Best of Talkin' Horses.