Steve Jordan will be celebrating his 64th birthday on Saturday; a day that could be made more exciting if I’ll Have Another should win the Belmont Stakes and become the first horse in 34 years to sweep the Triple Crown. But this will not be the first time Jordan’s birthday fell on a day when a Triple Crown sweep was on the line.

It happened on his 25th birthday in 1973. Jordan works out of Barn 4 on the Belmont backstretch as assembly barn coordinator. The “assembly” barn is where all horses must go before heading to the paddock prior to a race. The next barn over, about 50 yards away, is Barn 5, where Jordan worked for 16 years, first as a hotwalker and groom for Lucien Laurin, with whom he became very close, and then as assistant to Lucien’s son Roger.

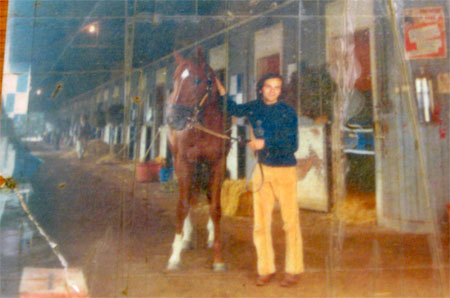

On his desk in Barn 4 are two treasured photographs – one of him walking Secretariat and the other holding Riva Ridge as the colt eyed an admiring kitten perched atop the fence post the morning after Riva broke the world record in the Brooklyn Handicap.

Steve Jordan and Big Red

Although it’s been nearly 40 years and almost everyone from Barn 5 is gone, the memories are still fresh in Jordan’s mind as he recalls one of the most remarkable periods in racing and sports history and the colorful cast of equine and human characters who became household names across the country.

This was the era of Secretariat; a name that still echoes through the chambers of time. And Jordan was there every step of the way.

When he wakes up on Saturday and crosses off another year on the calendar and prepares to witness history once again, he can think back to the morning of June 9, 1973 and the anticipation in Barn 5 and the feeling of just wanting to get the inevitable over with. Jordan and everyone else in the barn knew they were, as the Moody Blues would say, “on the threshold of a dream.”

They were ready and Secretariat was ready. Boy was he ready.

“(Exercise rider) Charlie Davis was walking Secretariat around the walking ring,” Jordan recalled. “We had a pony shed in the yard with a tree next to it. All of a sudden, Secretariat rears up and Charlie has his hands full trying to get control of him. We look up and there’s this photographer up in the tree. Secretariat obviously heard the click of his camera. We got him back in the barn and chased the photographer away. I was going, ‘Whoa, it didn’t take much to set him off; just the click of a camera.’ That’s how sharp he was. He was always a manageable horse, and if he wasn’t he could have easily tipped over as strong as he was. I knew he was ready to do something special.

“I said, ‘If anyone thinks Sham or anybody else is going to beat this horse today they have no idea what they’re in store for. I remember saying to a writer that morning, ‘:24 flat.’ He said, ‘You really think he’s going to get away with a :24 opening quarter?’ I said, ‘No, 2:24 flat.’ He looked at me like I was nuts and walked away.”

Jordan had a friend coming in for the race and they had seats in the clubhouse. He remembers watching Secretariat draw away “like a tremendous machine” and getting caught up the pandemonium like everyone else.

“As soon as he put Sham away, the grandstand literally started to shake,” he said. “The place was rocking. I had never felt anything like that before. You look at the fractions he’s putting up and you ask yourself, ‘Could this be possible?’ He just kept widening and widening. Even after all these years I still get chills watching it. I remember after the race, it was a feeling of relief more than anything.

“Everyone had been so confident leading up to the race. We all considered Sham a very good horse. Pincay had tried everything he could to try to beat Red, and you had to wonder, how much could he have left? But there were still people who believed Sham would beat Secretariat going a mile and a half. The few of us that are left will tell you that Secretariat really hadn’t learned how to run at that point. He didn’t learn to run until the fall of his 3-year-old year. In the spring, he was strong and exuberant, and it was almost like a young professional athlete doing everything just on talent. It wasn’t until the fall that we all said, ‘Now, this is really getting scary. He’s really starting to take this seriously.’ There’s no telling what he would have been as a 4-year-old. When he won the Man o’ War, he was amazing. Tentam was a really good horse and he tried him and tried him and Secretariat just flicked him away like a bug.”

Jordan had been living in Detroit and was a huge racing fan, following Riva Ridge through the 1972 Triple Crown. He had married his high school sweetheart, and she saw how strong the lure of the racetrack was to her husband, so she encouraged him to go to the track and get it out of his system. That summer he spent the month with his brother, who lived in Glens Falls, about 15 miles north of Saratoga. He went to the Saratoga backstretch looking for work, even though he had no experience working with horses. Of course, the first trainer he went to was Lucien Laurin, who tried his best to talk Jordan out of pursuing a life at the track. Each day they two would talk up in the clocker’s stand and eventually became close.

Finally, during the final week of the meet, Laurin asked him. ‘So, young man, what are you going to do now?’ Jordan told him he was going to look for a job either at Belmont or Monmouth.

An incredulous Laurin said, “I spent the whole month up here discouraging you from getting on the racetrack. It’s bad for family life, the hours are long and hard, and it’s very unrewarding initially. Why would you leave your hometown to do this?”

Jordan replied, “Mr. Laurin, I don’t live in Saratoga; I live in Detroit.” Laurin had no idea and he told Jordan, “Come by my barn Thursday morning and I’ll give you a job.”

And so, Jordan was thrust into a new world, a new life, and the biggest whirlwind ever to hit the Sport of Kings. He got to work with Riva Ridge, as well an up-and-coming 2-year-old named Secretariat. Years later, Philadelphia Daily News reporter Dick Jerardi interviewed Jordan and used the analogy of a baseball player coming out of the minor leagues and immediately becoming the centerfielder for the New York Yankees in the World Series.

Steve Jordan, Riva Ridge, and Friend

“No one at the time really knew the magnitude of what was happening, but it didn’t take long for everyone to realize something special was going on here,” Jordan said. “Of course, there was nowhere near the media scrutiny in those days as there is now, with Twitter and all the forms of communication and social media.”

What media pressure there was really started after Penny Chenery (then Penny Tweedy) syndicated Secretariat for a record $6.08 million. What people never knew was how close the Secretariat story came to going up in smoke, literally, shortly after the syndication.

“After the syndication, I never really noticed any difference in the day-to-day operation, although there was a bit more pressure having a horse worth that much money,” Jordan recalled. “I remember we were at Hialeah that winter. Greentree was stabled right behind us and Eddie Yowell and Del Carroll shared the barn right next us. One day, in the middle of the night, there was a fire in Yowell and Carroll’s barn and it burned down, with all the horses getting killed. It was so bad, Greentree’s hay nets caught on fire, that’s how close it came to us.”

Secretariat finally got to the races at 3, having to lug around that “Six Million Dollar Horse” title. He swept through the Bay Shore Stakes and Gotham Stakes with no problem, and then came his showdown with California sensation Sham in the Wood Memorial. The race proved to be one of the shockers of all time, as Secretariat and Sham not only both lost, the winner was Secretariat’s stablemate Angle Light. That was the worst possible thing that could have happened to Laurin. He had beaten his own horse, who was worth more money than any other horse in history. The look on Laurin’s face in the awkward winner’s circle photo pretty much told the story. He would have to answer to Penny, and he would have to answer to the fans and the syndicate members who were all prepared to witness the first Triple Crown winner in 25 years.

“What people didn’t realize was that Angle Light was a pretty good horse who had run some big races in stakes, had two mile and an eighth stakes under his belt, and was on the top of his game,” Jordan said. “No one chased him in the Wood. They paid no attention to him, and he just kept going. Lucien was sick to his stomach. He knew what the implications were having Secretariat not only lose, but finish third. That’s when the pressure really started, and rekindled the talk about Bold Ruler and the mile and a quarter. Things started to snowball from there, with the syndicate members now having doubts after believing he was going to win the Triple Crown.”

Of course, it was discovered later that Secretariat had an abscess in his mouth and wasn’t able to grab hold of the bit. Jordan, however, knew nothing about an abscess and said no one mentioned a thing about it.

“That’s a story full of conjecture,” he said. “I’m not saying whether it happened or didn’t happen, I only heard about it later on, so I had no way of knowing. Eddie Sweat (Secretariat’s groom) and I were close and he never hinted anything about that. But then maybe he was told not to. I really don’t know.”

The only thing anyone knew was that Secretariat had worked a mile slower than usual before the Wood, and wound up turning in an uncharacteristically dull race.

Secretariat’s next defeat came that summer in the Whitney at the hands of Onion, which was perhaps the biggest shocker of them all, considering Big Red had won the Triple Crown and followed it up with an easy victory at Arlington Park before breaking two track records in a workout in the mud at Saratoga, prepping for the Whitney. After the defeat, it was announced that Secretariat had a virus and fever and would miss the Travers. This time, Jordan knew for a fact that Big Red was a sick horse.

“He was definitely sick for the Whitney,” he said. “I can’t recall any trepidation going into the race, but most of the time these things explode from the stress of a race. And I’m sure he was incubating something going into the race. Afterward, we just walked him for eight to 10 days. One morning I was out grazing him, and back then we used only a single chain. Out of nowhere, he started raising hell and rearing up right near the old wooden manure pit. The first thing I did was look to see where my car was parked, because I knew if he got loose I’m going right to my car and saying sayonara to the racing game; I’m gone. I jumped inside the manure pit to brace myself, and he finally settled down. I was ashen and my heart was pounding out of my chest. I looked up and saw Penny and Lucien standing at the end of the shedrow and they’re both smiling. Lucien yells to me, ‘Stevie, you can bring him in now. I guess he’s feeling better, isn’t he?’”

Jordan had discovered earlier just how strong Big Red was when the colt lifted him off the ground just by sneezing.

The inaugural Marlboro Cup was getting close and everything had to go perfectly for Secretariat to make the race. The race initially was designed as a match race between Secretariat and Riva Ridge, but the Whitney defeat and a Riva Ridge loss on the grass took the luster out of that concept, and it was changed to an invitational, with the best horses in the country invited. But could Big Red make the race?

“One morning I was standing in the yard with Lucien and (assistant) Henny Hefner and Lucien said, ‘I don’t know, this is really squeezing on this horse to make this race after being as sick as he was. This is a big task facing all these good horses,’” Jordan recalled. “Henny always had a way of putting things in perspective, and he shrugged his shoulders and just said, “Well, boss, then we’ll just win in it with the other horse.’”

History shows that Secretariat, after turning in a brilliant final work, blew by Riva Ridge in the stretch and won the Marlboro Cup in world-record time.

“After the race, I was standing by the rail and Charlie Whittingham, who had Cougar and Kennedy Road in the race, was down there waiting for them to come back,” Jordan said. “Cougar (who finished a well-beaten third) came back first. (Bill) Shoemaker jumped off Cougar no more than five yards from me and pulled the tack off and just looked at Charlie, and all he said was, “Charlie, those are two runnnin’ sonofabitches that beat us.”

When Lucien Laurin retired, Jordan, who had also worked for a short while at The Meadow, became an assistant to Roger Laurin during the days of Chief’s Crown, whose groom was Eddie Sweat. He then went out on his own, training from 1986 to 2003 before returning to New York, where he worked as the Race Day Barn Security Coordinator. He remembers one year at Delaware Park, it was Kentucky Derby day, and he was saddling a horse he owned in a $5,000 claiming race and he was 50-1.

That was a harsh awakening that the days of Secretariat and Riva Ridge and the Triple Crown were long gone. But Big Red and Riva and Lucien and Penny and everyone in Barn 5 had become his family, and family memories remain vivid forever. As Jordan said, “You savor things whenever you can savor them and the years don’t take that away from you.”