The Triple Crown. As the years expand into decades, the feat of sweeping the Kentucky Derby, Preakness, and Belmont Stakes becomes more Herculean with each failed attempt, and those three words begin to take on more of a mystical quality.

While not as elusive at the Holy Grail, the quest to obtain the Triple Crown trophy and rediscover the glory of a time long passed continues to grow stronger. For those who witnessed Affirmed’s last Triple Crown sweep, it is hard to believe that a 40-year-old person today has no memory of an event that still seems so fresh in so many minds.

Prior to Secretariat, the well descends dramatically back to the glory days of the 1940s, when Count Fleet, Whirlaway, Assault, and Citation swept the Triple Crown. Those images are now captured only in rare black and white photos and decaying film footage.

We cannot even hope to capture the equine heroes of the 1930s, when the Triple Crown came of age. Gallant Fox, Omaha, and War Admiral are no more than imageless names that flow easily off our tongue, much like Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx, and all athletes, both human and equine, who helped supply moments of relief to a nation during the Great Depression.

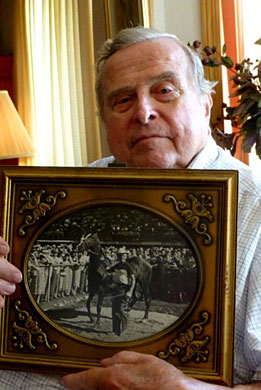

Although the portal back to those early years of the Triple Crown has all but closed, there still is one person around now who had the “honor and privilege” of caring for Omaha and developing a close friendship with him during the last nine years of the horse’s life.

For 87-year-old Morton Porter, the memories still are indelible, as he recalls those magical years with the only internationally renowned Triple Crown winner, who not only left his mark in America, but also in Great Britain.

“It was something to remember for a lifetime, and of course it’s certainly my only claim to fame,” Porter said from his home in Omaha, where he lives with his wife Mary and close to his four children and 10 grandchildren. “I have fond memories of the nine years I helped take care of him. It was a spectacular event for all of us out here because he was a truly famous horse, and every year that goes by and we don’t get another Triple Crown winner, it puts him in a more selective class all the time.”

Following his Triple Crown sweep in 1935, Omaha, trained by the legendary Sunny Jim Fitzsimmons, scored back-to-back victories in the Dwyer Stakes and Arlington Classic before being sidelined the remainder of the year with an injury. The colt’s owner, William Woodward Sr. of Belair Stud in Maryland had always wanted to race him in England, and in 1936, he sent him to trainer Cecil Boyd-Rochfort.

In his four starts in England, Omaha captured two races at Kempton, including the two-mile Queens Plate, before dropping a heartbreaking nose decision to Quashed in the prestigious Ascot Gold Cup, run over 2 1/2 miles. He concluded his career with a neck defeat in the Princess of Wales’s Stakes at Newmarket.

In England’s Observer Sport Monthly, the Quashed-Omaha Ascot Gold Cup was named the greatest race of all time, beating out the famous Grundy-Bustino King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Secretariat’s Belmont, the Affirmed-Alydar Belmont, and Arkle’s victory in the Cheltenham Gold Cup.

Jack Leach, a top jockey who became a racing writer for the Observer, wrote: “To see Quashed and Omaha battle out the finish of the Ascot Gold Cup took years off a man’s life, though it was well worth it.”

In remembering Omaha, the Daily Racing Form’s noted turf writer who went by the pen name of Salvator, wrote: “In action, he was a glorious sight; few Thoroughbreds have exhibited such a magnificent, sweeping, space-annihilating stride, or carried it with such strength and precision. His place is among the Titans of the American Turf.”

It was Porter’s father, Grosvenor (Grove), who owned a small horse farm and apple orchard in Nebraska City, about 45 miles south of Omaha, and J.J. “Jake” Isaacson, general manager of Ak-Sar-Ben Racetrack, who ultimately convinced Woodward to move the then 18-year-old stallion close to the city for which he was named.

Omaha had always been a favorite of Woodward’s, especially being sired by Belair’s pride and joy Gallant Fox, whose Derby, Preakness, and Belmont sweep in 1930 inspired Morning Telegraph columnist Charles Hatton to coin the phrase “Triple Crown.” Only Sir Barton in 1919 had managed to win all three races. Omaha remains the only Triple Crown winner to be sired by a Triple Crown winner, a feat not likely to be duplicated.

After standing at stud at Claiborne Farm and failing to become a top-class sire, Omaha was moved to small farm in Avon, N.Y., where he remained for seven years until 1950.

That is when Grove Porter and Isaacson went into action. The elder Porter had been instrumental in getting a law passed by the state legislature to conduct racing in Nebraska, and to be a non-profit organization, such as a state fair, where the profits from racing would go right back into the sport, rather than to some individual or private corporation. It was a unique law at the time.

Porter became a longtime racing commissioner, and is the only person ever to be named to the Nebraska Racing Hall of Fame and the Nebraska Football Hall of Fame. Morton continued in his father’s footsteps, playing football for Nebraska, as did his two sons.

“We’re the only three-generation family ever to play football for Nebraska,” Morton said. “One of my sons (Budge) suffered a spinal cord injury while making a tackle during practice that was considered a catastrophic injury, and he’s been paralyzed in a wheel chair, but is making a good life for himself.”

Morton was in college when his father and Isaacson finally convinced Woodward to move Omaha to Porter Orchards and Farm in Eastern Nebraska.

“Mr. Isaacson and my dad decided it would be wonderful to have the horse called Omaha in the state of Nebraska to stimulate Thoroughbred racing in this part of the country,” Morton recalled. “So, they approached Mr. Woodward and he nixed it right away. He said there was no way he would do that. It took maybe a year or two for them to soften the old boy up. He finally OK’d it, but stated we could only charge $25 for a breeding season, and we could only breed him to about 15 mares a year. It was just a matter of promotion to get people to breed to Omaha and show him annually at Ak-Sar-Ben Racetrack.”

Woodward also would not permit Omaha to be moved unless there was someone with him at all times. He was not to be placed in a crate, and had to be in a stall where he could move around freely. This is where Morton enters the picture.

A junior in college, it was Morton’s job to fly to New York, his first flight ever, and accompany Omaha on the train back to Nebraska.

“I went back with my dad and Mr. Isaacson,” Morton recalled. “We went to Avon, in upstate New York, and I got on a railroad express car with Omaha to take him back home. I built a partition at one end of the car and we came back on the train together; it was a wonderful, magnificent experience. I was blessed to be called upon to travel with such a great horse.”

Morton, who had ridden hunters and jumpers in horse shows when he was young, loaded hay, straw, and oats onto the car and off they went, chugging through six states. At every whistle stop, Morton would slide the doors open and let Omaha stick his head out. He would then tell onlookers and passersby about the famous Triple Crown winner that was passing through their town.

“Everyone loved seeing the horse and hearing stories about him,” Morton said. “At one point, I slipped out and got some lunch when the train was held up in Chicago for a little while, and, being an apple man, I got myself a couple of apples. I munched on my apple while he was happily eating alfalfa and he looked over at me like, ‘Boy, I’d like to have that.’ So I gave him the core, which he just devoured. Then I took the other apple out to eat it, and I looked at him and looked at the apple and decided to give him the apple. So, he took my second apple and the love affair began right there.”

When they arrived, there was a large crowd to greet the train. Once at the farm, there was a steady stream of visitors to see the great Omaha, who had now become the pride of Nebraska. Morton, who eventually took over the farm following his father’s death, was now the horse’s full-time groom and the two would remain inseparable for the next nine years.

Without top mares, Omaha had only limited success. Among his best progeny over the years were Bing Crosby Handicap winner Prevaricator and Louisiana Handicap winner South Dakota. However, his daughter, Flaming Top, became the great-granddam of England’s last Triple Crown winner, Nijinsky II, and his name can also be found in the pedigrees of three Kentucky Derby winners.

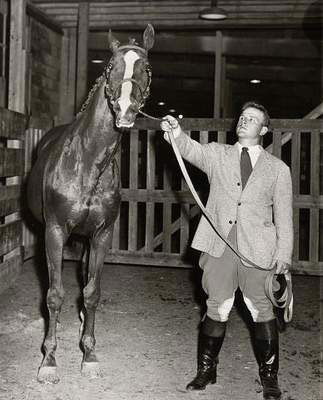

At least once, often twice, a year, Morton would take Omaha to Ak-Sar-Ben to show him off to the fans on Omaha Gold Cup Day and again at the Livestock and Rodeo Show, held in the adjacent arena.

“I would take him up there and parade him in front of the grandstand and lead him to the winner’s circle,” Morton said. “When the bell rang to start the race, he heard it, of course, and thought he was ready to run. It was all I could do to contain him. I had a shank in his mouth and a bridle and a bit and could barely hold him.

“Also, the floor of the winner’s circle in those days was sand, and one year it was a beastly hot day, flies were bothering him, and I know he was in misery with the heat, because I was. We were standing in front of the grandstand with a huge crowd looking on, and he wanted to roll in that sand. He’d start to go down and I’d take the crop and tap him with it. Finally, Jake Isaacson came down, and I told him I didn’t think I could keep him up very much longer; he wants to get in that sand. Jake says, ‘Well, go ahead and let him roll. We’ll hold up the mutuels until he gets done with it. If people like it, maybe they’ll bet more.’

“So, I let him roll, and you know, that old guy rolled clear over, which is unusual even for some young horses. He rolled over on his withers, got up on the other side and shook off some of the sand. That’s how he got rid of the flies. The people loved it.”

In October, Morton and Omaha would return for the livestock and rodeo show, which went on for 10 days. Morton would lead Omaha into the arena and walk him around in between events while the announcer would inform the audience of the horse’s accomplishments.

Although Morton and Omaha got along great over the years, there were times he had to be on his guard.

“He was a good friend and a lovable horse, but once in a while, though, typical of stallions, he could get a little bit riled up about something,” Morton recalled. “One time, it was way below zero one morning and I was brushing him and he reached down and grabbed my arm and if I hadn’t on about eight layers of clothes I think he would have pinched out a big chunk of flesh. When I undressed that night, I was black and blue from my shoulder down to my elbow. I don’t know why he did it, but he did. I smacked him for it, which I regretted. By and large, though we got along very well.”

Omaha continued to produce a small crop of foals each year. “We had a few broodmares and a few foals, and some people brought their broodmares to Omaha and we serviced them,” Morton said. “He was quite old then and it was no easy task to get that done. He was willing, and he did sire some promising offspring, especially hunters and jumpers. His grandchildren turned out pretty good. Of course, throughout his stud career he didn’t have any offspring that did anything close to what he did, but then again only 10 other horses have.”

By 1959, Omaha, now 27, still was pretty frisky and in good condition, but he was experiencing breathing problems, and Morton enclosed his stall and set up an oxygen tank, which gave him some relief. But on April 24, Omaha died in his stall.

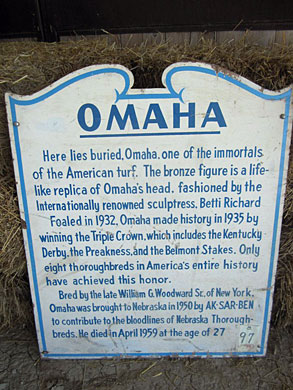

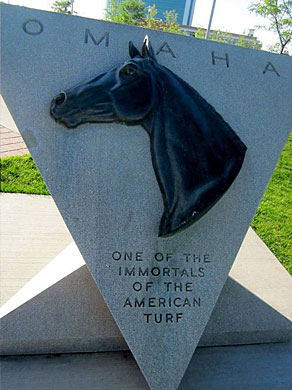

“It was his time I suspect,” Morton said. “I really missed him. He had become a part of the family, and I have so many fond memories of him. I loaded him on a truck and took him to Ak-Sar-Ben, where he was buried right near the grandstand, with a stone monument and wooden grave marker. When the track built a clubhouse addition, the excavation was going to be right over the site where he was buried. We decided not to exhume the body and move it; this was the track he loved and where he was meant to be. They moved his monument and marker to the Circle of Champions near the grandstand entrance and displayed them there until the track closed down (in 1996).”

On the track’s site now is a real estate development called Aksarben Village. In the village, occupied by businesses, restaurants, and partially owned by the University of Nebraska Omaha, is Stinson Park, a small park-like area that now is the site of a historical marker and the stone monument that was moved there from the Circle of Champions. But the wooden marker that contained a lengthy tribute to the horse was not moved to the park.

One person who took a huge interest in the location of Omaha’s grave site was Janice Kehler Hollister. The Belair Stable Museum informed her that they knew nothing about Omaha’s life in Nebraska or of Morton Porter. She then began her search for the original wooden grave marker and a portrait of Omaha on suede in an oval frame that Ak-Sar-Ben had auctioned off when they closed. It was learned they had been purchased and given to Horsemen’s Park, a first-class simulcast facility that conducts three live racing days a year. The oval painting currently is on display at the track, while the wooden marker was located by the track’s caretaker in an old shed out in the mud on track property, lost and forgotten. With the help of Cindy Curran, Horsemen’s Park’s social media director, who was instrumental in finding the marker, it is currently being restored and will also go on display.

According to Nancy Castilow, assistant to the chancellor at the University of Nebraska Omaha, there is no way of ascertaining whether or not Omaha’s remains are on the former Ak-Sar-Ben property that is now owned by the university. Where his remains are located will forever remain a mystery.

As for Morton Porter, he and his wife have left the farm and now live in Omaha in order to be closer to their family.

Omaha, like his remains and grave marker, has been long forgotten. He has never been accorded the respect due a Triple Crown winner. In the Daily Racing Form’s “Champions,” book, there is a photo of every Triple Crown winner except Omaha. In 1935, there was no official Horse of the Year Award, which began the following year. But, although Omaha was recognized as the 3-year-old champion, it was the 4-year-old Discovery, who had defeated Omaha in the Brooklyn Handicap, who was recognized as Horse of the Year, making Omaha the only Triple Crown winner not named or recognized as Horse of the Year that same year. Part of that can be attributed to Omaha running back against older horses in the Brooklyn only two weeks after winning the Belmont Stakes. And this was after running in the Withers Stakes in between the Preakness and Belmont.

But what was most important to the horse was the respect and love he received from his longtime friend Morton Porter, and all the special moments they shared on the farm and at Ak-Sar-Ben.

“Those were fun times for me,” Morton said. “I can look back now, but I didn’t know at the time how great and special they really were. Every year around the Triple Crown, especially when a horse is trying to sweep all three races, people call and ask about Omaha. He deserves the attention.”

Morton is proud of his children and grandchildren and the life he has provided them. But he also takes great pride in something else; the one thing that defined him:

“I was the groom for Omaha.”

Morton Porter holding photo of him and Omaha at Ak-Sar-Ben. - Photo Cindy Curran, Framed Photo Ak-Sar-Ben Race Track

Morton Porter getting ready to parade Omaha at the Livestock and Rodeo Show. Photo Omaha World-Herald

Omaha in his earlier days as a stallion.

Omaha's wooden grave marker that has been found and restored. - Photo Cindy Curran

Morton Porter prepares to show off Omaha at Ak-Sar-Ben. - Photo Ak-Sar-Ben Race Track

Stone monument saluting Omaha at Stinson Park. - Cindy Curran