It was 40 years ago, July 29, that a mean spirited 2-year-old named John Henry, who had sold for a paltry $1,100 and then $2,200, toppled over a fallen horse during an overnight handicap at tiny Jefferson Downs in Louisiana. Fortunately he somehow emerged unscathed and the rest as they say is history. But this chapter in John Henry’s life is far more profound for the effect the horse would have on the life of his then trainer Phil Marino. This is their story, as told in my book, “John Henry.”

For the first two years of his life, John Henry had been peddled like a cheap wristwatch. All the polishing couldn’t hide the fact that he was liable to stop ticking at any time. Sure, his stride and professionalism led some to believe that maybe there was a fine piece of machinery beneath the surface. But the bottom line was the colt had a mediocre pedigree, being by a sire who stood for a $500 stud fee, was not much to look at, had a major flaw in conformation, and was a savage in his stall. His legs had been used more as weapons than as instruments of speed.

But if John had one positive trait, it was his ability to touch people’s lives. And regardless of his early misadventures, none of his owners ever lost money with him. Of course, everyone knows how John affected the lives of Ron McAnally and Sam Rubin, but no one’s life was affected more by the horse than Phil Marino’s.

When Marino and his client Colleen Madere came to Bubba Snowden’s farm in Kentucky with the intention of purchasing John Henry on the recommendation of the Murty brothers, Marino wanted to take John out to the track and breeze him himself. When he went to the barn to get the horse, the first thing he noticed was a 55-gallon drum of molasses shoved up against the front of his stall door.

“There was all this banging and screaming going on in the stall, Marino recalled. “I said to myself, ‘What the hell did I get myself into?’”

But John Henry’s groom convinced Marino he would be fine once he got the bridle on him. Of course, it would take him 10 minutes to catch him.

Marino loved what he felt when he smooched to John, and was convinced he had a great deal of class. Madere offered Snowden $11,000 for the horse with the stipulation he get him ready to run and okayed out of the gate and then ship him to Jefferson Downs.

Snowden had finally gotten rid of John Henry, who he had bought at auction for $2,200 and twice had the horse sold, but had to take him back both times when the deals fell through. Snowden had his own misadventures with John Henry, as did the horse’s previous owners, Jean and John Callaway, who bought him for a meager $1,100. When John Henry left the Callaways for the sale, Jean remembers him raring up like a wild horse and her saying “good riddance.” In describing him, John Callaway used the words “retarded,” “crazy,” and “weird,” which seemed appropriate considering how John Henry would take out his anger on his water buckets and feed tubs, ripping them off the wall and stomping on them.

After John arrived at Jefferson Downs, Marino, like everyone before him, discovered the keg of dynamite that had just been delivered to his barn. Marino had aluminum feed buckets, and in the first week alone, John put his feet through seven of them after he finished eating. Marino replaced them with plastic tubs and just left them on the floor of the stall. The good news was that John didn’t tear them up. The bad news was that the stalls only had partial partitions, and when Marino arrived each morning, John’s feed tub was three or four stalls down the shedrow in another horse’s stall. He had managed to grab it and fling it over the partition. Marino eventually gave John a soccer ball to play with, and he would squat down on his knees and bat it around. Then, once he was finished with it, he’d kick it out of the stall. But Marino also discovered that once he put the bridle on John, Mr. Hyde quickly turned into Dr. Jekyll.

“He was a pussycat,” Marino said. “He was such a ham it would take me forty-five minutes to get him to the track. He’d just stand there and look around. And on the way home, he’d stop and graze along the way.”

Because John was so “nutty” and constantly getting into trouble, Marino nicknamed him “Squirrel.” Although John behaved once the bridle was on, getting it on could be quite an adventure. Unlike most trainers who used rubber tie chains, Marino’s were chain link, the kind you’d use to tie up a bicycle. He would double it and hook it to the wall, and John still would try to rear.

“He’d get up and try to jump on top of you and paw and kick you,” he said. “And he’d bite you while you were doing him up. But he never hurt anyone. He was very calculated about everything he did. He just wanted to let you know who was the boss.”

When Marino started breezing John Henry, he knew he had a runner on his hands. In between works, whenever they got to the top of the stretch, Marino would let him gallop out strong to the wire. Soon, an outrider had to come pick them up. John had learned that when he came to the head of the stretch, it was time to run. The first time Marino worked him from the gate, he broke with a promising two-year-old, trained by Sal Tassistro, who had already won for $50,000. The two hooked up at the break and John beat Tassistro’s horse, blazing the three-eighths in :34 flat. And Marino never even asked John to run.

Marino had been so impressed with John Henry he told Colleen Madere, “I’m gonna win the Lafayette Futurity with this horse.”

“She thought I was crazy,” Marino said. “So did everyone else. I kept braggin’ on him all the time, and they all thought I was nuts saying that about a horse who hadn’t even raced.”

Finally, on May 20, 1977, John Henry was ready to become a racehorse. Once those gates opened to launch his career, all his nefarious deeds would be put behind him. Marino, who had only four stalls, was stabled in the same barn as Bernie Flint. Even though Flint had thirty horses and was among the leading trainers at the meet, purses were negligible, and both he and Marino were struggling to eke out an existence.

Flint also had a horse, named You Sexy Thing, in the race, a four-furlong maiden special weight event at Jefferson Downs.

“Bernie bet the last fifty dollars he had in his pocket on his horse,” Marino said.

“Those were rough days,” Flint added. “With maiden purses only $2,800, you had to bet your horses and just go out there and work hard every day. Phil was just starting out and doing most of the work by himself. Jefferson Downs was the last place you’d expect to find a future champion. I remember John Henry as this gangly thing who was mean as hell.”

With Marino’s bragging and the horse’s fast works, John Henry was sent off as the 17-10 second choice. John broke a bit slowly from the rail and settled into fifth. At the eighth pole, he still was four lengths off the lead and appeared beaten. But under the hard driving of jockey Glen Spiehler, John showed the courage and tenacity that would become his trademark and just got up at the wire to nose out You Sexy Thing.

“After that race, we knew we had a nice horse on our hands,” said Marino. “Mrs. Madere was happy, because she also bet quite a lot of money on him. But the atmosphere in the winner’s circle was more professional than anything else.”

John ran well in his next two starts in allowance company, but could only manage a second and a third. Then, on July 29, he was entered in a six-furlong handicap. On the far turn, a horse went down in front of John, who was unable to avoid the fallen horse and toppled over him. Miraculously, John wasn’t hurt.

Soon after, Marino put him in another overnight handicap, and it began to look as if John’s misfortunes were carrying over onto the racetrack. Shortly after the break, all the lights went out, and there was chaos on the track, as horses and jockeys scrambled about aimlessly in the dark.

“Oh, God,” Marino said from his box. “He’s ruined. He’s gonna get hurt.”

When the lights came back on, three jockeys were injured, and two horses had run through the gap, one jumping into the nearby canal and the other running loose in the barn area. And there was John Henry standing at the seven-eighths pole with the rider on his back.

“It looked like he was standing there posing for pictures,” Marino said. “He never turned a hair.”

The race was ruled no contest. After winning an allowance race by three lengths, John was entered in a trial for the Lafayette Futurity, the race that Marino predicted months earlier John Henry would win.

In the paddock, Madere told Marino, “Just qualify with him. I’m very superstitious about going into a big race off a win.”

“I told her, ‘You tell the jock that. I’m in here to win it,’ ” Marino said. “When he finished second (in the trial) and still had the second-fastest qualifying time, I knew I was a cinch to win the Futurity.”

For the next ten days, Marino slept on a cot in front of John’s stall to keep an eye on him. John still managed to rip his eye, just above the eyelash, but it was nothing serious.

That year, the winner’s purse for the six-furlong Futurity was a record $43,225, a fortune for a trainer at Evangeline Downs. The morning of the race, Marino snuck out on the track at 4:30 and blew John out an eighth of a mile.

“It was the fastest eighth I’d ever gone on a horse,” he said. “I knew right then and there he was gonna win.”

John was sent off at 5-1 and broke from the rail in the twelve-horse field. The track had come up sloppy due to a driving rain storm, and jockey Alonzo Guajardo was able to settle him in fourth, five lengths off the lead. At the eighth pole, he still had two and a half lengths to make up. Like in his debut, John dug down and gave it everything. With hurricane-force winds and heavy rain blowing in his face, he closed relentlessly, just getting up to win by a head over Lil’ Liza Jayne.

“That night we were flying high,” Marino said. “We all went out to dinner and Mrs. Madere ordered a case of champagne.”

Marino felt like he was on top of the world. John Henry had come through for him, and everything seemed right with the world. But then the stable moved to Fair Grounds, and that’s when, as Marino said, “All hell broke loose.”

John Henry completely lost his form. On the surface it looked as if he simply couldn’t handle the jump in class from Evangeline and Jefferson. Marino and Madere began to argue constantly. Marino tried to tell her John just couldn’t handle the track.

“The first time I ran him, in the Hospitality Stakes, he finished fifth and came back like he had run forty miles,” Marino said. “And I knew he was fit.”

Marino told Madere, “Either there’s something wrong with him or he just doesn’t like the racetrack.”

One bad race after another followed. Marino called noted Kentucky veterinarian Dr. Alex Harthill to come look at John and had blacksmith Jack Reynolds put new shoes on him.

“Everyone said there’s nothing wrong with him,” Marino said. “They all concluded it was the racetrack. I kept trying to relay that to Mrs. Madere, but she didn’t want to hear any of it.”

John Henry had now turned three, and Marino decided to stretch him out to two turns, hoping that would help turn him around. It didn’t, as John threw in two more dull performances. After one of the races, he returned to the barn and was given a bath. Marino started walking him, and before he knew it, his jacket sleeve was in John’s mouth. John picked Marino up off the ground and took off down the shedrow, dragging him along. Marino was being lifted in the air and was completely helpless.

Fortunately, Mike Petrie, a trainer who shared Marino’s barn, grabbed John and was able to stop him, as John finally let go of his trainer.

“Thank God I had a goose down jacket or he would have taken a big chunk out of me,” Marino said. “That’s how mad the horse was. You could tell something was bothering him. He simply was pissed. I kept relaying this to Mrs. Madere.”

Marino tried everything. Blinkers didn’t work, nor did dropping him into claiming races. Twice John ran for a $25,000 tag, and once for $20,000. The best he could do was a third-place finish.

Since his victory in the Lafayette Futurity, John Henry had run nine times, finishing out of the money in seven of them. It was now late March of his three-year-old year, and the horse’s future looked bleak. It seemed a return to the bush tracks was all that awaited him. Had John Henry’s demons finally sealed his fate?

Madere’s patience was wearing thin. In early April, Marino had made arrangements with a friend, trainer James Navarre, to send John Henry to Oaklawn Park, where he’d have a stall for him. At five in the morning, the van was outside the barn at Fair Grounds, with all the tack loaded. Fifteen minutes later, Marino received a call from Madere telling him to cancel the trip.

“She owned a poodle parlor, grooming dogs,” he said, “and she told me they had too many dogs to groom, and that she couldn’t make the trip. I said to her, ‘Mrs. Madere, I’m twenty-seven years old. I think I’m qualified to follow a van 350 miles up the road. She said, ‘Where he goes, I go, or he don’t go at all.’ ”

Marino had had enough. He told Madere that the van was loaded and ready to go somewhere.

“I’m not running him at Fair Grounds again,” Marino said. “So, if he’s not going to Oaklawn, then van him up to Keeneland and sell him.”

That was the end of Marino’s relationship with Madere, as the two decided to part. John Henry had no trainer and no place to go, so Madere turned to the only person who could help. Instead of going to Oaklawn, John wound up heading back Keeneland, to none other than Bubba Snowden.

Madere had called Snowden and told him they couldn’t do any good with John Henry and asked if he could sell him...again. She told him that the vets couldn’t find anything wrong with him.

“I don’t want to send him to anyone but you,” she said, “because you know his disposition.” So, John Henry returned to Snowden, who took X-rays of the horse’s knees and ankles. He was perfectly sound, and Snowden asked Madere what she wanted for him. She said $25,000, but he told her it would be very difficult to sell a horse for that price when he had just been beaten for that amount, and finished up the track running for $20,000.

She told him to try, but no one was interested. Snowden then offered a swap. He would take John Henry in exchange for a couple of two-year-olds — a colt and a filly. Madere agreed and John Henry belonged to Snowden for the third time. (He eventually would sell him to a Jewish bicycle salesman from New York named Sam Rubin, who when told he had bought a gelding, said, “What color is that?”)

For Phil Marino, the John Henry saga was far from over. The horse he had trained, groomed, exercised, and slept with would become a national hero, earning a record $6.5 million and winning seven Eclipse Awards, including two Horse of the Year titles, while he was forced to come to terms with his lowly existence.

The more successful the horse became, the deeper Marino would sink, until he hit rock bottom.

“It ruined me,” he said. “It was like they pulled the plug on me. I really didn’t care about anything and started drinking and doing drugs. I had a few horses, but every morning I’d get up and look out my tack room door, and I’d see nothing but $2,000 claimers looking back at me, while this horse is out there winning five hundred thousand and million-dollar races.”

Marino’s days at Evangeline Downs, in particular, were a nightmare. He was stabled there when John Henry won his two Arlington Millions. After each race, the same taunting announcement was made over the loudspeaker: “Phil Marino, John Henry just won another Million. How are you feeling today?”

“Whenever I’d try to hustle clients, I’d get the same thing: ‘Oh, you couldn’t win with John Henry. How are you going to win with my horse?’ ” Marino said.

Marino couldn’t take it any longer. Life as a Thoroughbred trainer had turned into a living hell, and he descended deeper into drugs and alcohol. He drank a fifth of vodka a day and had to support a $2,400-a-week cocaine habit.

“This went on through all the years John Henry raced,” Marino said. “I was labeled as the man who couldn’t win with John Henry. Every time he ran I crawled deeper and deeper into my hole, and I really didn’t care if I lived or died.”

Then came the day in 1985 that changed Marino’s life completely. It was just another hot July morning, with another empty day awaiting him. He was at the home of his jockey, and the two had gotten drunk the night before. When Marino awoke the next morning, he found the rider passed out on the floor. He turned on the radio, and remembers it was exactly 7:38 when he heard the news of John Henry’s retirement.

“I pushed the vodka and cocaine away, and I haven’t had a drink or taken a drug since,” he said. “It was like a veil had been lifted off my head.”

Through his ordeal Marino never stopped caring about John Henry. “We always had a special relationship,” he said. “And we still do. I visit him at the Horse Park at least six or seven times when we’re stabled in Kentucky. He still comes running over to me when I call him Squirrel. We had a game we played when he wasn’t trying to kill me. I’d take the palm of my hand and he’d open his mouth where just his teeth were showing. I’d push the palm of my hand against his mouth and we’d play like a tug of war back and forth. And we still do to this day. Every time I go see him, I pull off a little piece of his tail and give it to one of my friends. And I always give the girls there some money to make sure he has enough carrots. Even after all these years, and all I went through, whenever I visit old John, he still brings tears to my eyes.”

Marino built up a successful stable, with the support of owner Sandi Kleemann, and leased a farm in Kentucky. “I was blessed when Sandi Kleemann came into my life as an owner,” he said. “Mrs. Madere never called or stayed in touch with me. I heard she passed away a couple of years after we lost the horse. The Good Lord put me to the test. He taught me humility and made me a better person. He took me from the lowest depths to the top of the world.”

On February 26, 2009, Phil Marino passed away at age 59 at his home in Maryland following a lengthy illness. I thank him for sharing his innermost thoughts with me and the demons that plagued him for so long. He had out-lived the horse that nearly ruined his life by two years. But John Henry kept proving too ornery to die and lived to the ripe old age of 32. This is just one of many remarkable chapters in the life of John Henry, who despite his irascible disposition became one of the most beloved horses of all time.

*********

Epilogue – After finishing this column I learned of the death earlier this month of Bobby Donato at age 79. It was Donato, a former vice squad detective for the Philadephia Police Department, who purchased John Henry for Sam Rubin and first put him on the grass.

John Henry was still as cantankerous as ever, biting everyone who came close to him, but his groom, Pablo “Junior” Cosme, had a Labrador retriever named Opie who became good friends with John and would sleep in his stall, practically right up against him. John would playfully nip at Opie on occasion, and that would help settle him down.

When Donato started galloping John Henry on grass, he noticed how he would just glide over the surface. The day after Affirmed and Alydar’s epic battle in the Preakness Stakes, John Henry made his first start for Donato and Rubin, winning a six-furlong claiming race. If someone had told you that in addition to Affirmed and Alydar, there would be another future Hall of Famer running that weekend you would be hard pressed to find him in the second half of the Aqueduct daily double, running for a $25,000 claiming tag.

After Belmont opened, Donato found a $35,000 claiming race for John Henry’s grass debut. John was like a kid frolicking over this new surface, his legs in perfect unison, no cracks of the whip, no jockey shouting at him, just the sound of his own feet skimming over the grass. John just kept going, winning by 14 lengths.

Donato was thrilled but apprehensive as he dashed down to the track, his elation tempered by feelings of uncertainty and fear. He knew the monster he had just unleashed might be spending that night in someone else’s barn. All he kept saying was, “God, I hope I didn’t lose him.”

The claim box was empty. For the eighth time in John Henry’s young life, someone had blown an opportunity to own one of the greatest horses of all time.

“Needless to say, John never saw another claiming race again,” Donato said.

But it was Junior Cosme who said it best: “After that race, he became John Henry.”

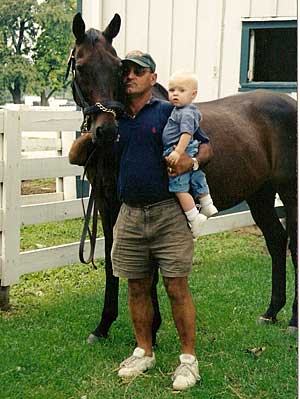

All is forgiven, as Phil Marino brings his grandson Chase to meet John Henry

Photo courtesy of Tammy Siters