It was a two-avenue block walk to Flatlands Ave. in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn. You knew the schedule, so it was never a long wait for the Pioneer bus to arrive. The bus arrives pretty much on time. You walk on, pay the fare and are immediately engulfed by the smell of cigar smoke.

I have never taken a puff of a cigar, but the smell is intoxicating, bringing me back to my childhood and Ebbetts Fields and my Uncle Sam’s cigars, and then later Yankee Stadium and then the old Madison Square Garden on 50th Street. Those were the special places of my youth where the smell of cigar smoke blended so perfectly with the smell of beer and mustard. Soon those three aromas would come together in the grandstand of Aqueduct Racetrack, which was only eight years old when I first inhabited it in 1967.

I was 12 years old when this spanking new colorful modern structure sprung to life a stone’s throw from the Belt Parkway. I had no idea what it was as we drove past it back in 1959, only that it reminded me of a baseball stadium.

Now, here I was eight years later a young man of 20 waiting on the corner for the bus who would take me to paradise; to the magical world of Thoroughbred racing; a world that would in all essence save my life. Aqueduct, known as The Big A, was the racetrack of the future, as busses, cars, and even trains converged on the track, which was the only track to have its own subway station.

The bus ride was one of hope and bravado for the mostly grizzled occupants, their heads buried in the “Telly,” known officially as The Morning Telegraph. You had to get a head start on your handicapping if you wanted to bet the Daily Double, of which there was only one, on the first and second races. Many racetrack goers would rush to their local newsstand the night before to pick up the Telly and get a real early jump on their handicapping. This was a time of 24-hour entries, and candy stores and newspaper shops that would get the Telly delivered every night.

Making the Double was a ritual for some people. When that last train pulled into the station before post time for the first race, people would come rushing off and making a mad dash to the windows. There is the story of this guy running off the train and getting to the windows seconds before the betting closed. He slapped down his money and frantically said to the mutual clerk, “Gimme anybody.”

This was before OTB (Off-Track Betting) back when the Telly was 60 cents and the racetrack was the only place to wager, unless you had a bookie. It was before exactas and quinellas and trifectas. You bet win, place, or show or you simply skipped the race and went on to the next one. The only way you could make money betting races with big favorites was hope the racing secretary did his job in weighting the horses. Handicaps were an important part of racing, as it was the only way to bring the horses closer together at the finish. If it wasn’t for handicaps and racing secretaries having the freedom to assign outrageous weights, superstars like Kelso, Buckpasser, Damascus, and Dr. Fager would rarely have been beaten. As it is, they rarely were anyway. They truly were Saturday’s heroes. Oh, yes, there was no Sunday racing.

Back in those days the three most popular sports in the country by far were baseball, boxing, and horse racing. College football was more popular than professional football, which did not begin to make an impact until “the greatest game ever played” between the New York Giants and Baltimore Colts in the 1958 championship game and then through the ‘60s with the Green Bay Packers’ dynasty and the birth of the AFL and the NFL expansion team, the Dallas Cowboys. Professional basketball also did not begin to surge in popularity until the late ‘60s.

So, every Saturday, the Aqueduct grandstand was packed with 50,000-plus fans. On holidays like Memorial Day, Fourth of July, and Labor Day, the crowds swelled to 60,000 and 70,000. Belmont Park was being rebuilt (starting in 1962) and The Big A was the only game in town.

The feature back then was always the seventh race, and you could begin to feel the anticipation grow by about the fifth race. You got one stakes and that was it. But, boy, were those stakes special. New York was the hub of racing and just about every equine star ran there.

My roots in racing were not very deep. I remember two guys on a bus one day talking about Swaps and Nashua. I was fascinated but paid little attention. Then in the sixth or seventh grade my teacher made reference to a horse named Tim Tam. Great name I thought, as we used to have crackers called Tam Tams. And then there was Carry Back, who was the talk of the town after winning the Kentucky Derby and Preakness. He seemed like an unbeatable force, coming from far back and charging to victory. I couldn’t imagine why all horses didn’t run that way. Seemed so logical to me. Then in 1963 our class had a raffle on the Kentucky Derby. Everyone wanted to draw No Robbery, because he was owned by the owner of the New York Mets. I drew a horse named Chateaugay that I couldn’t even pronounce. I tried to sell him off but there were no takers. And of course, there were the Sunday papers that seemed to have the name Kelso in the headline every week.

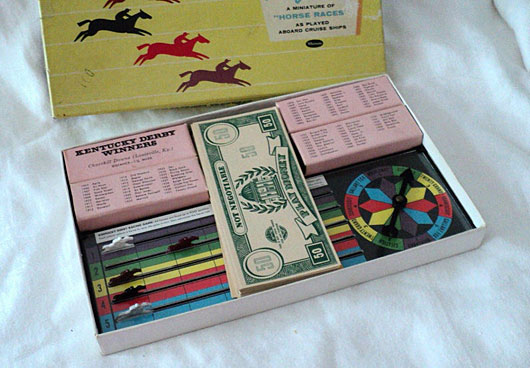

I can’t remember who bought it for me, but I had a game that I loved, despite its ridiculous simplicity, called “Kentucky Derby Racing Game.” It consisted of a straightaway racetrack, a spinner, play money, and five tiny plastic color-coordinated horses named Citation, Whirlaway, Twenty Grand, Gallant Fox, and Seabiscuit. You spun the arrow and whichever name it landed on, you moved that horse up a space. It was totally mindless, but I loved playing it, despite Citation winning almost every time.

Unlike racing today, the vast majority of fans came to the track equipped with binoculars. There were no replays until the late ‘60s. It was through those binoculars that you recorded and preserved all images for posterity. Your memories of the aforementioned Kelso, Buckpasser, Damascus, and Dr. Fager and all your favorite steeds were of live horses right before your eyes, their glistening coats and distinctive silks a vibrant blur in the sunshine, the sound of their hooves pounding the track, and cool breezes blowing in your face, and, yes, the smell of cigars, beer, and mustard wafting through the grandstand. It was all live, all real, and all beautiful.

This is what awaited me as the Pioneer bus neared Aqueduct. It pulled into the parking lot and stopped to let everyone out at the far end of the grandstand by the top of the stretch. You entered, walked up to the top level and found your seat. It was still early, so the grandstand was still fairly empty and you had your choice of seats. First there was silence, then the slowly growing murmur of the crowd, and finally the silence was interrupted by the distinct high-pitched voice of track announcer of Fred Capossela welcoming the crowd and announcing the scratches.

And then came those familiar words from “Cappy” we all waited for, “The crowd gets close to the rail, and that means one thing…it is now post time.”

As most are aware from my previous columns, Damascus, with his spectacular move, pouncing on his prey in cat-like fashion, was God-like to me, replacing all my boyhood heroes from baseball and hockey. He had been instrumental in opening this new wondrous world up to me. And Dr. Fager was his arch rival who ran with reckless abandon like some wild mustang with fire in his eyes. He was the enemy and I feared him. I will never forget the sound of Cappy’s voice announcing to the crowd on July 4th, 1968 in that familiar cadence, “Ladies and gentleman, your attention please, in the seventh race (the long-awaited showdown between Damascus and Dr. Fager in the Suburban Handicap), No. 1A, Hedevar (Damascus’ pacesetter) has…been…scratched.” The buzz in the grandstand that followed can still be heard in my mind today.

I usually sat somewhere in midstretch, yet close enough to dash down to the paddock to see the horses. But by then there was a mass of humanity on the apron, and you had to weave your way through the crowd early enough to get a spot relatively close to the paddock. By the 1970’s I was already working at The Telly and now spent my days in the clubhouse for a few extra bucks.

The Pioneer bus ride back home was a totally different scene, as most of the occupants spent the whole trip rehashing their tales of woe and triumph, mostly complaining to no one in particular, but everyone as a whole, about the ones that got away, about the nose defeats, about the bad rides by that “bum” Cordero or Baeza or Ycaza or Belmonte or Rotz. The only thing that was the same as the ride going to the track was the cigar smoke.

One of the most exciting days of the year was opening day at Aqueduct in March, a day that was widely anticipated all winter. What spectacular horses and amazing feats would we witness this year? It was the harbinger of spring, the beginning of a new chapter, not only in racing, but of your life. Working on Wall Street, a familiar sight on opening day were the partners of your firm leaving work early to head for the track, many of whom owned horses. I managed to attend most of the opening days, which usually were sunny, with the colorful tulips spread around the paddock. Horses vacationing in the North all winter or running at Bowie in Maryland or returning from Hialeah all converged on the Big A. All was again right with the world.

The track was like being around family. Yes, you had your favorite superstars, but also your favorite allowance horses and claimers. You knew them all. I remember falling in love with a gorgeous jet-black colt named Shakazu, owned by Cragwood Stable, because he was right there in front of me in the flesh and his beauty captivated me.

Yes, these are days long gone. The world has changed, and surely racing has changed. The Telly is gone, binoculars are gone, rushing to make the Double is gone, the concept of superstars carrying staggering weights is gone, the great 4-year-olds and 5-year-olds are gone, opening day at Aqueduct is gone, the crowded grandstands are gone, and, yes, the Pioneer bus is gone. But half a century later I can still smell those cigars and the beer and mustard. Horse racing still envelops my life. Well, at least it is trying to.